THE GREAT GREEN ISLAND WAS ON FIRE.

The Germans bombed Britain and Ireland night after night for over seven months. Between September 7, 1940 and May 16, 1941 there were seemingly endless tons of explosives dropped on the civilian population of Britain. London was attacked 71 times, Birmingham, Liverpool and Plymouth eight times; other cities were hit hard as well. It has become known to history as The Blitz, but what it was in fact was a relentless, single-minded, incendiary attempt to bring the land of legendary kings, Newton and Locke, Shakespeare and Dickens to its bloody knees.

Into this apocalyptic whirl of hell-fire a young man was born. It was not a serene spot in which to enter the world, but then his childhood years were rarely easy, starting at the very beginning, birthed into this ring of fire. His mother named him, in part, after the steadfast, cigar-chomping prime minister who shook his fist toward the skies, at the death-wielding pilots of the Nazi regime.

Only three months prior, another boy, once known as Richard, was born in the same city. Not the strongest of children, he was struck by a number of illnesses in his early years. Two years later, in June of 1942, with Britain still on its heels, another boy, in the very same Southwestern working class city, christened James by his mother Mary, came into this world at war. His father was not home for the birth, he a volunteer firefighter in a time of much burning. Then, eight months later, a fourth child was born, and his parents named him George, after the King; he the last of the four children of Harold Hargreaves Harrison and his wife Louise.

The four boys and their families survived The Blitz, and the war. Britain became great again, and won the war, having vanquished the greatest foe in all its storied, thousand-year history.

Three of the boys became teenage friends, starting making music together, and found themselves, a mere fifteen years after this cataclysmic war ended, performing in the back alleys of Hamburg, Germany, the very same country that tried to destroy their homeland during their childhood years.

It was that thing beyond ironic. And it -- their coming together, their singular music making and so much that followed -- wound up being as history-making as the world war that preceded the quartet they created and the songs that they wrote.

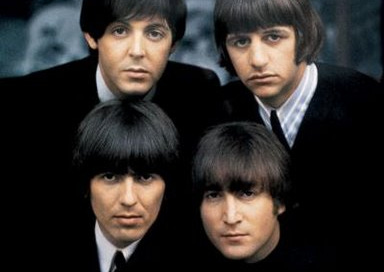

In the fall of 2012 it was exactly 50 years since the Beatles first hit the charts, and we know much about this world famous band and about each band member, John Winston Lennon, Richard Starkey a.k.a. Ringo, James Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

But history is about time, and perspective. With the vantage point of a half-century, one can well ask, aside from their dozens of unforgettable songs and their indelible influence on Western culture (and in Russia, and Japan, and South America too), what their place in history might be. In what ways did these four lads from Liverpool -- born in a time of massive destruction, with their nation hanging within a hair of its very existence -- change not only rock and pop music, how did they change the world, our world, in the 1960s and up to this day?

In 2012, in mid-August, I drove my then-14 year old son home from two weeks of sleepaway camp in upstate New York. The CD from the Cirque d’ Soleil hit show LOVE was playing (it being a wonderful remix of some of their greatest music), and my son was singing along to all the songs even as he played a game on the iPad. At one point he murmured out loud, “The Beatles are timeless.” His simple comment to no one in particular pleased me greatly, not only because we were both singing along in spots, and not only because he knew the words to songs written over thirty years before he was born, but because he had stated aloud the very thing I had just been thinking: “Yes, they really were that great.”

The Fab Four was no fad. They were, and remain, the very opposite of a passing style; another fad in a culture of endless, evanescent fads.

So, if the human race does not hit the Big Wall, and actually survives this wild cyclone of a century, yes, the odds are great that come the year 2112, or even 2400 and beyond, our (presumably still-human) descendants will not only be listening to Bach, Beethoven and Mozart, but to Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra and the Beatles as well, and maybe even singing along to Eleanor Rigby, as my young son did.

For the foreseeable future and well past, the Beatles’ legacy is set, musically-speaking. But beyond the music, what? Past Hey Jude, Here Comes the Sun and other harmonies, what else did they leave to us, and to history?

One answer is surely a rare genus of startling rebirth. Although coming in the aftermath of a devastating war, the aural greenery and colorful new growth produced by four young men is no less astonishing. Who would imagine — a mere 17 years after the world’s bloodiest conflict — that a quartet of mop-topped musicians could do what the Furher could not? You know, conquer the world.

There’s an even bigger answer, I think. The Beatles took the lead in a new form of social compact, one with a noticably different perspective. At its best, it augered in a sweeter kind of shared, transnational peace, with a sometimes softer light on the lot of us. At the very least, we were offered a more agreeable view of human accord, and what's possible, along with a terrific soundtrack.

Seriously? Yes, seriously.

I do think future historians, not just future music lovers, will look very kindly upon the Beatles and The Sixties, that endlessly experimental, wildly clad (and often unclad) Go-Go decade in which they came into ascendance. Perhaps not a great new dawn, but a major pivot point. Forget the Age of Aquarius. Think arms linked with strangers as well as friends.

After the Beatles’ brief pop reign, the world became a slightly better place for our wayward species. A small planet got a little smaller, and tighter. Tighter, as in tied together, slightly less hard, and more expansive.

Out of the mass murdering, wickedly destructive war they were born into, they birthed and handed to the rest of us not only a high caliber songbook, but something else, something larger. From these four lads we received a gift basket of lovely lines and peace-laden themes, splashes of wit and whimsy, sure. As for that larger thing, I’ll call it a great coming together, as in a newly refashioned harmony, the likes of which are rarely seen in this world. Foreign shores seemed less far away. Other cultures became other than Other.

One small example: it’s not lost on many of us that the Beatles introduced Ravi Shankar and the otherworldly sounds of the sitar to the West, they also introduced many millions to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Transcendental Meditation. They swung open the door to many things Indian, especially its psychedelically-hued spiritual culture, which very much includes yoga as well as meditation.

Several renown Indian yogis brought yoga to worldwide prominence by the middle to late 20th century. But another, perhaps larger bridge of this great cultural transmission came courtesy of the American Beats and the Beatles. How many less people would be attending yoga classes in Europe and America today, or practicing meditation – whether TM, at Zen retreats, or at home with a candle -- without the Beatles’ trip to India, and all they brought back with them? Who knows?

What we do know is that these musical Marco Polos brought Indian culture closer to the West by many a mile. India itself went from British colony to feisty Independent two decades before George Harrison first used a sitar as a background instrument in the song Norweigan Wood. Decades prior, near-saintly Gandhi earned special adoration around the world. But India got its first real taste of modern, global rock star status after John, Paul, George and Ringo came and went in early 1968.

Will the world be fundamentally changed with many millions of people in almost every country now taking yoga classes, doing meditation and other mindfulness practices? We can’t know unless we time travel and take a peek. But my guess is that advanced education for young people worldwide does make a difference, and for the better. In the same vein, metaphysical fitness, no less than physical fitness, will have a real impact on our divergent, increasingly interdependent world. The benefits of yoga and meditation are more than just personal. They can be decidedly global and political, too.

Now, I’m getting older, and quickly, but I’m not daft. Yet. I know what happened in the world since the Beatles broke up in 1970. Since then, America alone has been involved in Vietnam, Somalia, Iraq twice, Bosnia, the War on Terror, Afghanistan – not to mention all the other internecine conflicts and awful bloodshed in Africa, the Mideast, Sri Lanka, Asia and elsewhere.

So what’s different now?

While more attracted to vampires than ever, we are perhaps a little less bloodthirsty than we were in the mid-20th century, and surely since that vast, horrific war over 70 years back. But we are still the premier killer species, especially of each other. Our evolution over the last 50 or 75 years can be measured in micro-meters, if at all.

That duly acknowledged, the world has also changed significantly since WWII, and not only in regards women’s rights, civil rights, and because of mass communications, technology, the Web and social media. It changed because of how many of us remain profoundly anti-war — or surely anti-violence — and far more likely to grab onto new ideas from different cultures, seeking commonality and friendship with others who were once called, and considered, Foreigners.

This all matters I should think, and for this profound change in our global community, I give the four lads from Liverpool a fair share of the credit and a large round of applause. Really.

Why? Because they not only inspired millions of teens and 20-somethings around the world to start garage bands, and they not only influenced hair length and style, they laced their lyrics and their collective being with joy, playfulness – and acceptance. Specifically, acceptance of our frailties and our silly quirks. But all the more so, acceptance of our great potential as a human family to come together and give it a go. The Lads gave us permission to keep playing past 20 with a cheeky glee, sharing the fun, and sometimes the love, and with a larger group of fellow Earthlings. They had us sing a little ditty together or laugh about how absurd so much of it all is, and in doing so gave the rest of us not just their charm and wit but a feeling of shared perspective. That, and a larger community. A much larger community.

The Beatles, and our response to them, helped to reset our collective compass; at their best even placing a strong damper on our automatic instincts, which we all know can be quite bad. 50 years after Love Me Do made it to number 17 on The Record Retailer chart in the U.K. in October of 1962, we are not a different species than we were all those years ago. After screaming wildly to She Loves You, and later swaying in peaceful, shut-eyed joy to Hey Jude, we have not gone from little Mussolinis to little Gandhis. But we are different.

Most of us who are over 40, in the privacy of our beings or in certain quiet moments, feel that we are somehow better people after the best of what we experienced in the 1960s, and that the world has moved a bit closer, and to no small extent that change was catalyzed by four musicians from Liverpool, born during World War II, who brought us, in its deadly wake, a little more peace and reconciliation, a whole lot more joy, and a significant boost in what used to be known as Human Potential.

( © 2012 Ken Taub)

Very good read and projection onto out recent century here on this small but precious planet. Interestingly framed and substantiated, Ken.